Chester Barnard’s Four Spheres of Morality

Chester Barnard has authored a great book titled ‘The Functions of the Executive’ which presents a theory of cooperation and organization. This book was published in 1938. The book is noteworthy for its focus on how organizations actually operate. The book is considered as one of the first books to focus on leadership from a social and psychological viewpoint.

Barnard’s philosophy and thought processes in writing the book were characterized by humanism, empiricism, speculative philosophy and analysis of the contrasting nature of individualism and collectivism.

Barnard was a student of Harvard University between 1906 and 1909 where he majored in economics. However, he did not obtain a degree. He joined AT & T Corporation and rose through the ranks. Barnard became president of New Jersey Bells which was founded in 1904 as an AT&T’s arm serving southern New Jersey, named Delaware and Atlantic Telegraph & Telephone Company. Barnard served the company as President between 1927 and 1948. At New Jersey Bell, Barnard enjoyed “long hours of self-absorbed reflection and study.

He describes the four spheres of morality in his book:

The Commitments of Private Life: This the first sphere of morality. In this part Barnard describes the manager’s duties and obligations which are usually stated as intangible yet universal principles. Always tell the truth, keep your promises, never hurt others, be good to everybody these morals are taught to us from childhood. Individuals get puzzled when it comes to organizational role to be played by them; many people disagree about the origins of these moral duties. Such principles, however, offer only an abstract, mitigated view of philosophers. The morals are very complex to practice. It comes in way in a person’s commitments, ideals and aspirations. Morality is a man-made concept that is defined by the society you live in; it is subjective.

Yet hard moral choices are at times unavoidable for many people in positions of power. How do you fire a friend, someone you have grown up with for years? How do you evaluate performance of one of your relatives who works under you? How to violate an employee’s privacy with a drinking problem, for example how to intervene in his private life to get him help which he badly needs? Can you be at peace when your company’s product will be misused by some customers and hurt innocent people? You have clear conscience; you don’t like to pay bribe, but you are forced to pay bribe to get a work done for your company. These and so many more examples describe the personal life sphere of an executive. Executives are always struggling to clear moral dilemmas while doing their jobs.

The Commitments as Economic Agent: the second sphere of morality in a manager’s life is the role of an economic agent. Managers need to create profits for the organization. An executive works to improve economics of a firm. The management of the firm and his superiors often remind him to serve in the interests of shareholders. What is realized rarely is that the manager is loaded with so many other responsibilities to stick in the framework created by the organization; he is responsible for legal, financial, HR, marketing etc. The ties between the owners of a company and the managers who act as their agents are unavoidably moral. Shareholders entrust their assets to managers, and managers promise, implicitly to work for the shareholders’ interests. Like any other promise, this relationship of trust carries strong moral weight. Moreover, this obligation is strengthened by the duty that all citizens have to obey the law. For the sake of profits, on few occasions managers compromise on their values which disturb their personal lives.

Commitments as Company Leaders: This is the third sphere of responsibility which exists because employees and managers are members of organizations which is compared to human body and therefore it is said that organizations do not have permanent status. In the wake of new economy, where value comes increasingly from the knowledge of people, and where workers are no longer undifferentiated cogs in an industrial machine, management and leadership are not easily separated. People look to their managers, not just to assign them a task, but to define for them a purpose. And managers must organize workers, not just to maximize efficiency, but to nurture skills, develop talent and inspire results.

Managers need to act as per situation; there is no permanent style of leading leaders must manage show as per demand of a situation. They need to show lot of flexibility while managing challenging and difficult situations. They need to command, demand, inspire, prompt, mentor, guide, coach, sell ideas, take part, act, build, and sometimes even reprimand. Often the leadership style may change as per need of the hour

The late management guru Peter Drucker was one of the first to recognize this truth. He identified the emergence of the “knowledge worker,” and that created profound differences the way business world was organized.

The fundamental sustaining style of leadership is that there is no ‘best’ or ‘worst’ style of leadership. Effective leadership is task-relevant, and the most successful leaders are those who adapt their leadership style maturely. Matured leaders set high but attainable goals, they are willing to take responsibility for the task. They are best learners; they learn from each situation and mold themselves.

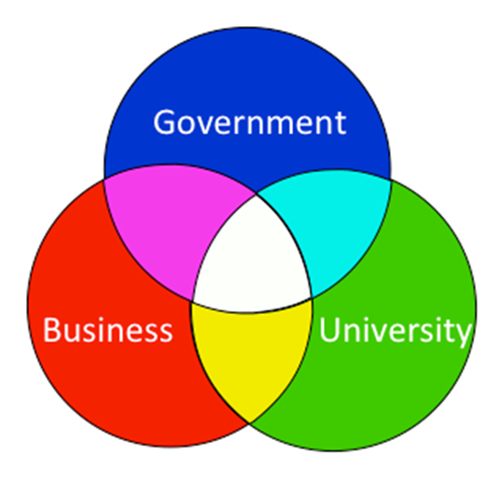

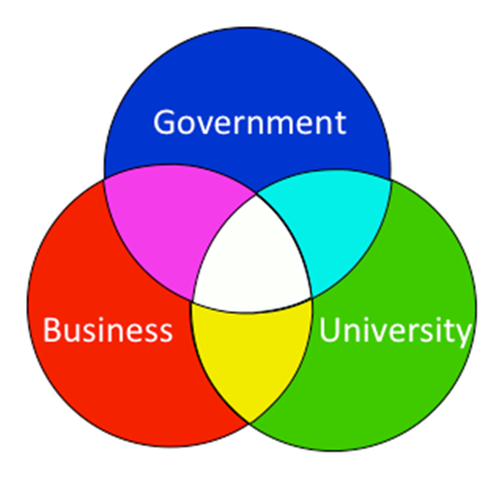

Responsibilities beyond Firm’s Boundaries: it is natural to think that executives’ responsibilities stop at their organization’s boundaries. But firms do not exist in vacuum. And they have complex relationships with government agencies, labor unions, with strategic alliance partners, distributors, customers, suppliers, and even competitors. Globalization has blurred national boundaries. This organizational reality creates a new and enormously complex sphere of responsibilities for managers. Again, the central issue is power. Just as business executives have enormous influence over the people inside their company, they have the power to create influence outside their company because of their operations and sometimes their destinies which are tangled. In Japan, West Germany, and other countries, groups of large and small firms are clustered in the form of cartels, keiretsu (a conglomeration of businesses linked together by cross-shareholdings to form a robust corporate structure) and other confederations. America, despite its ideological preference for the Adam Smith model of small-firm competition, is home to many of the largest firms in the world, and they, too, are surrounded by vast cadres of suppliers and customers and often have close relationships with many government agencies.

For the sake of clarity I would like to give an example of global firm Nike. NIKE owns no factories for manufacturing its footwear and apparel, which make up ~88% of its revenues. Instead, manufacturing is outsourced to third parties because of the cost advantages of doing so. Most raw materials in NIKE’s supply chain are sourced in the manufacturing host country by independent contractors mostly existing in Asian countries.

Conclusion: Globalization has stimulated changes in all aspects of human endeavor. Therefore, everywhere, people, institutions, roles, statuses, organizations etc, are changing. Changes are therefore inevitable consequence in any organization. It has been argued that change is the very essence of the environment in which an organization operates. A change is any deviation from normal situation and its management requires special skills to weather the change.

Most people get confused with their faulty thinking of unethical behavior; they think that “bad” people do “bad” things and “good” people are ought to do “good” things. This good-bad tagging of people that we do misleads us in most situations. The moral dilemmas of managers are many. They keep battling conflicting moralities among different spheres of responsibilities. Each sphere is, in many ways, a nearly complete moral universe comprising of its own world of commitments, human relationships, strong duties, norms of behavior, personal aspirations, and choices that bring happiness and suffering to others. When a manager faces problems simultaneously in different spheres of commitment, he faces the hazards of which Chester Barnard has warned in his book.