The concept of economic complexity in a country refers to the production of domestically-based knowledge products as well as the volume and diversification of export goods by a country. Economic complexity means the emphasis on technical knowledge and its application in goods and services produced by a country. It also means the intense application of technical knowledge in product diversification to encompass it in the domestic consumer markets on one hand and foreign markets on the other. However, the economic complexity of countries’ production is not limited to the ability to apply knowledge to the production process rather it encompasses much broader dimensions. Therefore, the more varied the country’s export basket is, it is considered more refined and more powerful in terms of economic interfaces at the international level. More exports bring in more economically viability with it.

In today’s global economy, consumers are used to seeing products from every corner of the world in their local grocery stores and retail shops. These overseas products come with imports which provide more choices to consumers. And because they are usually manufactured more cheaply than any domestically-produced equivalent, imports help consumers manage their strained household budgets.

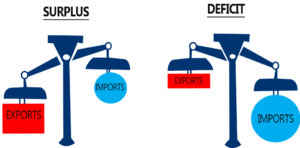

When a country’s imports is bigger than the exports in terms of volume and it distorts a nation’s balance of trade and devalues its currency. The devaluation of a country’s currency can have a huge impact on the everyday life of a country’s citizens because the value of a currency is one of the biggest determinants of a nation’s economic performance and its gross domestic product (GDP). Maintaining the appropriate balance of imports and exports is crucial for a country. The importing and exporting activity of a country can influence a country’s GDP, its exchange rate, and its level of inflation and interest rates.

The Atlas of Economic Complexity is a 2011 economics book by Ricardo Hausmann, Cesar A. Hidalgo, Sebastián Bustos, Michele Coscia, Sarah Chung, Juan Jimenez, Alexander Simoes and Muhammed A. Yıldırım. The book attempts to measure the amount of productive knowledge that each country holds, by visualizing the differences between national economies. The book’s originality is to go beyond standard statistics by making use of “complexity statistics” of 128 countries. The book concludes that it is difficult and a complex task for a country’s government planners to kick-start new industries, entrepreneurship development, new products, intellectual property rights etc. The book is accompanied by two websites that host interactive visualizations and expand upon data featured in the book.

The visualizations presented in The Atlas were created in the observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), a data visualizations engine created by Alex Simoes and Cesar A Hidalgo in the Macro Connections group at the MIT Media Lab. The Observatory of Economic Complexity was launched in 2011. In 2013, Harvard’s Centre for International Development released an autonomous version of the platform, entitled The Atlas of Economic Complexity. The Harvard version builds on the original code base developed by Alex Simoes at the MIT Media Lab and uses a different method for cleaning the data than the OEC. The Atlas is distributed under a creative commons license which makes it free for non-commercial use.

The Economic Complexity Index (ECI) is a holistic measure for calculating the productive capabilities of large economic systems, usually cities, regions, or countries. Higher economic complexity as compared to country’s income level drives economic development. Countries that are home to a great assortment of productive know-how, particularly complex specialized know-how, are able to produce a great diversity of sophisticated products.

Countries that are able to sustain a diverse range of productive know-how, including sophisticated, unique know-how, are found to be able to produce a wide diversity of goods, including complex products that few other countries can make.

A prediction of how much a country will grow based on its current level of Economic Complexity, its Complexity Outlook or connectedness to new complex products in the Product Space, as compared to its current income level in GDP per capita and expected natural resource exports. Economic complexity alone helps explain the lion’s share of variance in current income levels. But the value of economic complexity is in its predictive power on future growth, where a simple measure of current complexity and connectedness to new complex products, in relation to current income levels and expected natural resource exports, holds greater accuracy in predicting future growth than any other single economic indicator.

A rank in ECI of countries is based on how diversified and large their export basket is. Countries that are home to a great diversity of productive know-how, particularly complex specialized know-how, are able to produce a great diversity of sophisticated products.

Highly ranked countries in EC tend to have these attributes: a high diversity of exported products, sophisticated and unique exported products, in short, the ranking hinges on the concept of “productive knowledge” or the implied ability to produce a product. The top 10 export countries are China, United States, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Hong Kong, South Korea, Italy, France and Belgium. Collectively, those leading exports-based economies represent over half (52.3%) of total exports by value from all countries.

India’s biggest export products by value in 2020 were refined petroleum oils, diamonds, pharmaceuticals, jewelry and cars. India main imports are: mineral fuels, oils and waxes and bituminous substances, pearls, precious and semi-precious stones and jewelry electrical machinery and equipment, nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery and mechanical appliances, and organic chemicals.

More exports mean more production, jobs and revenue. GDP increases when the total value of goods and services that domestic producers sell to foreign markets exceeds. If a country exports more than it imports, there is a high demand for its goods, and thus, for its currency. The economics of supply and demand dictate that when demand is high, prices rise and the currency appreciates in value.

The Economic Survey says that while the government is already doing the “heavy lifting”, its India’s private sector that needs to step up. The Indian government already has tax incentives for corporates contributing to R&D. The Chief Economic Advisor KV Subramanian said that the tax incentives in the past have been more liberal than other countries but it didn’t bring about a great participation from India’s private sector.