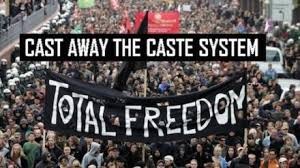

Ms. M.A. Sneha, an advocate aged 35

years in Tirupathur, is the first Indian citizen without a caste and religion.

In fact, since her birth she has remained without any caste or religion.

Whether it was her birth or school certificate, the columns on caste and

religion remained blank. In February 2019, the Tamil Nadu government issued

Sneha a formal certificate that she is a caste and religion less person. She is

the first citizen in the country to be formally certified so. She says that it took

her nine years to acquire this ‘no caste, no religion’ certificate. Kudos to

this young lady!!

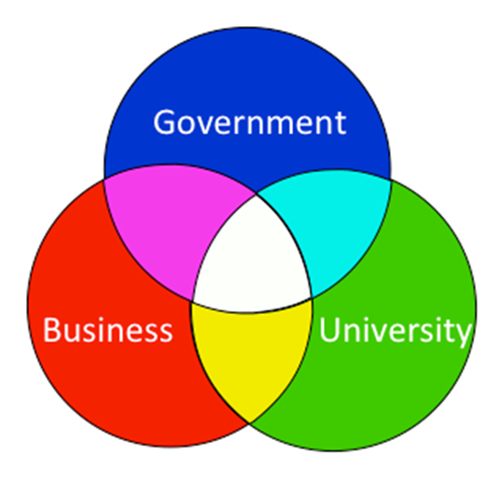

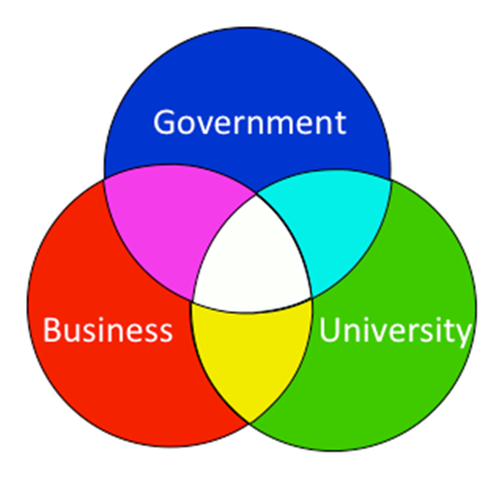

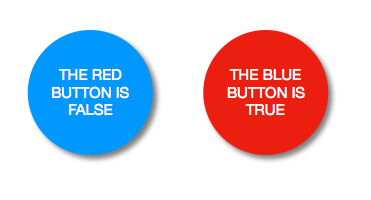

Inherited caste identity is an important determinant of life opportunity in India, but is not given the same significance in global development policy debates as gender, race, age, religion or other identity characteristics. While caste systems deal with social structures within the physical world, religion is focussed more on the metaphysical. Caste systems are based on systems dealing with hierarchical issues, while religion is focused on metaphysical issues such as divine worship, morals, and ethical issues.

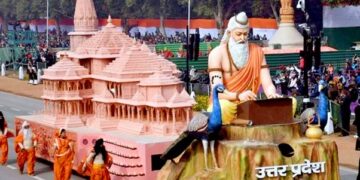

India’s caste obsession is well known in the world. The caste system is literally wired into the Indian mindset. For centuries it’s a natural part of life, and removing it is quite painful job. For ages in India, especially Hinduism divides the people into four classes: the Brahmins, the Kshatriyas, the Vaishyas and the Shudras. This system was used to help the Hindus administer their cities with adherence to a strict hierarchy. The priests hold the top of the hierarchy, who controlled everything, with the warriors below them, who fought wars with the approval of the priests. Then there were the merchants and traders, who helped feed and clothe the city, and then the workers, who were treated literally like slaves.

Similarly a long time ago, on the opposite side of the world, in a nation known as the United States of America, there were two racial groups, the ‘whites’ and the ‘blacks’. The whites had advantaged backgrounds, many of them directly or indirectly descendants of people from Europe, the Civilised Land. The blacks had a more inferior background. They came from the Savage Land, Africa, and had been brought by the whites by payment (just as one buys apples or peanuts from a department store), to work for them as slaves. This continued for almost two centuries until one day Abraham Lincoln, President of America announced that slavery has to come to an end. It came down real hard on the practitioners of slavery, so they separated, beginning a Civil War, which still echoes in the US to this day. However, the practitioners lost, and they were forced to finish slavery, but didn’t do so without setting up laws, known as the ‘Jim Crow’ Laws. Jim Crow laws were state and local laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern United States. All were enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by white Democratic-dominated state legislatures after the Reconstruction period. The laws were enforced until 1965.

Here in India’s caste system and ‘untouchability’ have been a matter of profound interest to a large number of social science researchers, historians, and even the general public in modern times. Perceptions of Indian caste have taken such deep roots in the minds of non-Indians that often when we travel to other countries we are mocked. Questions are asked which caste we belong to; whether it’s an upper caste or lower caste during casual conversations. Frankly speaking, not enough attention has been paid to history of social hierarchy in India.

Caste-based reservation was introduced by the British Raj and continued by independent India. It covers higher education, public sector employment and legislative representation, applying to Dalits, Adivasis and Other Backward Classes. Our Constitution-makers introduced reservation only for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in jobs and in admissions to colleges, and that too for ten years after India was declared independent. It was decide that possible extensions would be given to give equal chance to the backward caste and tribes if need be. They rejected Dr. Ambedkar’s suggestion that it should be for a fixed period of 30 or 40 years, with no provision for extension. Thus, the system has been extended every ten years, for nearly 70 years.

In my opinion, when the world is progressing at such a faster pace in technology, science and other walks of life, does caste really matter? I am happy to see that youngsters don’t care …….but, they face the harsh reality in terms of reservation in education and jobs.

The Indian politicians want to hold on the caste card tightly. It is sad but in each and every state of the country, we can find that election is fought on the basis of religion and caste.

We do not possess a real general definition of caste. It appears to me that any attempt at definition is bound to fail because of the intricacy of the phenomenon. On the other hand, much literature on the subject is marred by lack of precision about the use of the term. Sardar Patel, the Home Minister during the political integration of India and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, addressed the nation to rise above caste and religion, because it will rapidly disappear. We have to speedily forget these things. But, can we?