Micro finance matters in the lives of poor people. They matter in the same way that Community Development Finance Institutions (CDFI) matter here in the United States: they provide suitable financial services to low-income and excluded segments on affordable and responsibly delivered terms.

Street vendors selling vegetables, fruits, ready-to-eat street food, tea, cloth and handloom, beauty and fashion accessories, footwear, artisan products, barber shops, cobblers, paan shops, laundry services, house maids, gardeners, carpenters, electricians, plumbers and many more micro service providers and entrepreneurs have suffered uncountable despairs in the pandemic. Covid-19 related lockdowns forced the aforementioned entities to shutter business either temporarily or permanently.

In Indian metro cities street hawking is considered as a peril which prevents movements on roads, it impedes the development of the cities in many ways. But, hawkers are essential for our daily survival in big cities, their presence cannot be ignored. Though street vending is one of the oldest forms of retail in our country, the urban laws of India still neglects the activity and its practitioners. City municipal corporations continue to regard hawking as illegal. There are sections of the public who feel that hawkers intrude on spaces meant for civic use, and others just want to prohibit the hawkers from doing business for reasons known to them. Even those who may be buying goods from street vendors, protest against them whenever municipal corporations vacate them from roads and footpaths.

Clearing streets, footpaths and transport terminals of vendors and hawkers, and confiscating their goods, is a daily municipal activity. For their part, the street vendors continue to claim their space in the cities to earn their living. We have seen rags to riches stories and cases of street hawkers. Many have become rich due to their diligence and business sense.

Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs) are a type of NBFC that focuses on the financial requirements of the poorest people in the country, primarily in rural areas.

The Reserve Bank of India is the institution’s sole regulator. The primary goal of establishing the Indian microfinance business was to provide financial inclusion to the poorest and more backward sections of society.

Since microfinance primarily serves the weaker sections of society, over indebtedness by such borrowers is a common and one of the significant problems of microfinance in India. Borrowers are always in need of money; therefore they borrow from all available sources.

For the street hawkers four types of loan schemes are prevalent in Mumbai. These schemes are based on the daily repayment method and loans are provided for 33-days, 66-days, 100-days and 200-days by moneylenders. I wish to mention one particular case of the 33-day loan in Matunga, Central Mumbai which caught my attention. Muthu is a 45 years old vegetables vendor selling vegetables on the footpath of Matunga market. He is Hindu belonging to the general caste and is illiterate. He is married with a dependency burden of ten members. His daily earnings are around Rs 600. His wife works as domestic help in the same area and earns about Rs.10,000 pm. Muthu wanted to borrow a sum of Rs 10,000 for 66 days few days ago under the Rs 200 per day scheme. But, the amount he got actually was around Rs 9,500. Even though, he got Rs 500 less, he had to pay Rs 13,300 (66×200+100) to the moneylender. The moneylender extorted Rs 500 from him and forced him to pay Rs 13,300 at an exorbitant interest rate. The glaring fact about micro finance compared to commercial banks is commercial banks charge 8-12%, MFIs charge a significantly high-interest rate 12-30%.

This news item is from Mint: in February 2020, unaware the coronavirus pandemic was about to wipe out her livelihood, Arpita Das borrowed $2,300 to buy materials and equipment for her family fishing business in West Bengal, India. A few weeks later, demand for her prawns collapsed, leaving her unable to make the $180 monthly repayments to two micro lenders. The 33-year-old mother of two, who’d never missed a payment since she started borrowing three years earlier, is now living off the vegetables and grains she grows on a plot of land outside the home she shares with her husband and his parents. With the whole family out of work, they’re unlikely to have any income unless she can borrow $1,400 for this year’s prawn harvest.

During India’s initial three-month lockdown, she started getting harassed by the lenders. They used to call her regularly to see how she was doing. Later the representatives started visiting her in person at home every few weeks to see if she can pay. Das said she feared she may be forced to turn to moneylenders, who charge rates as high as 100%. This fact is so disturbing. Microfinance lenders use muscle power, rowdy and unethical means in loan recovery. They are the different breed altogether.

Most borrowers are small traders, street hawkers, and daily wage labourers, the people most vulnerable to the economic shocks of the pandemic as well as to the virus itself. In India many escaped from urban slums to rural villages soon after the lockdown in late March 2020 with no idea when or how they will be able to support themselves, let alone pay their debts.

After the lockdown-like curbs were imposed in most of the states in India, lives of people were relieved because of street vendors. The vendors sold goods in limited time which facilitated lives of people.

Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014 is an Act of the Parliament of India enacted to regulate street vendors in public areas and protect their rights. The bill received the assent of the President of India on 4 March 2014. The Act came into force from 1 May 2014.

The notification, issued by the Urban Development Department on April 29, stated the scheme will benefit all eligible hawkers. Similar assistance is also being extended to auto rickshaw and construction workers. It will also cover the street vendors who had submitted an application seeking a loan of Rs 10,000 under the PM SVANIDHI financial package.

In a cat-and-mouse game, local officials ignore hawkers when convenient and tighten the rules on them when exigencies have demanded preventive action. This has served a dual purpose: some underhand money goes to the administration for turning a blind eye, and the street vendors get to conduct their business too. With time, hawkers found able allies and protectors among local councillors who objected to their eviction and instead promoted their proliferation. Hawkers returned the favour by turning into loyal voters and political workers. A complex calculus emerged: hawking was bad under the law, but the law did not find any takers. While hawkers dared it and breached it, buyers ignored it and abetted its breach. Local politicians benefitted as it helped perpetuate their career, and administrators ignored the implementation of the law, tempering private profit with local exigency. Consequently, street hawking continued to ‘thrive’ illegally in every Indian city.

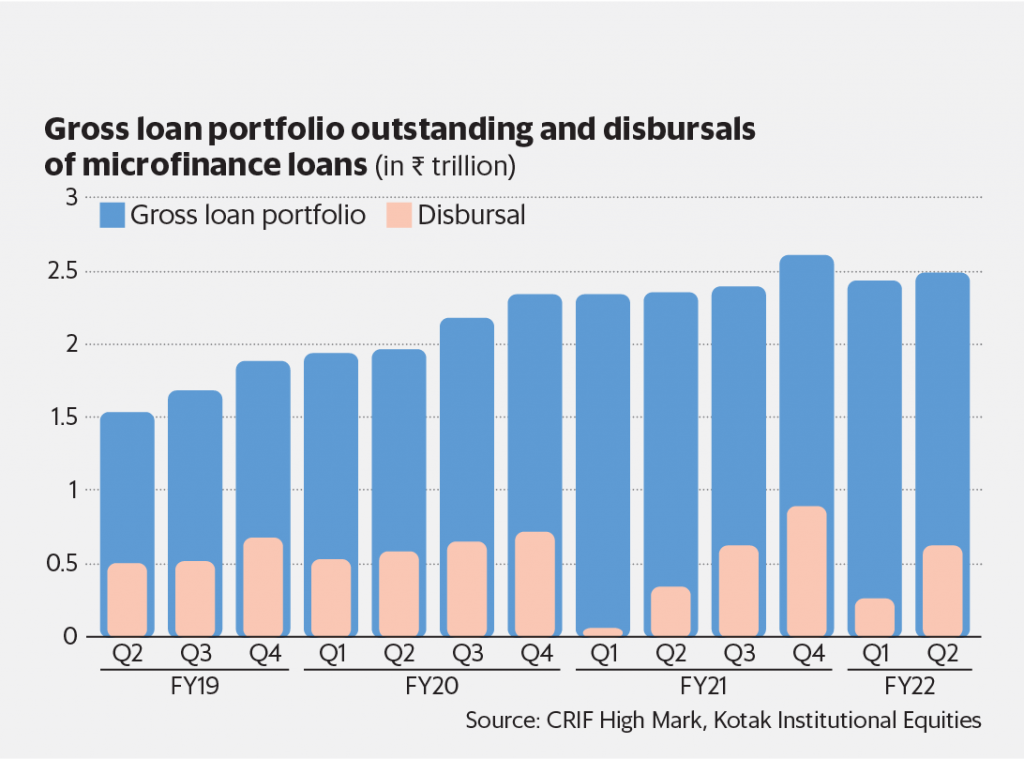

Millions of street vendors in a fast-urbanising India continue to face this struggle, which seems to have only intensified in the recent decades. Gross loan portfolio stood at ₹2.6-lakh crore as of March 31, according to Crisil. Small loan specialists in India that typically cater to people without bank accounts are facing a jump in pandemic-related defaults that could force some of them out of business, industry experts warn.

After the setbacks during the second wave of the pandemic, the microfinance industry showed an improvement in disbursements, asset quality and new loan inquiries in the September 2021 quarter, a report says.

Another fact is that the micro finance portfolio outstanding for the industry, which typically provides small ticket loans to micro entrepreneurs and women borrowers. Women are more committed in repaying the loans. The loans increased to Rs 249 lakh crore as of September 2021.

Loan collection efficiency across the total loan pool has fallen to about 70 per cent from a peak of nearly 95 per cent in March, analysts say, indicating a potential build up in stress. The gross loan portfolio of India’s microfinance lenders stood at ₹2.6-lakh crore ($35 billion) as of March 31, according to Crisil.

Banks and nongovernment organizations also provide microfinance loans. Microfinance institutions, or MFIs, can be set up with only Rs50 million ($685,000) and can lend as much as Rs125,000 per borrower. The micro lenders themselves borrow from banks and nonbank lenders at an average 14%, and then charge interest rates of as high as 22%. Moneylenders aside, informal financial groups which are not registered as credit agencies also operate all over the nation. A major part of credit borrowing by vendors is through money lenders.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has impressed upon public sector banks (PSBs) the need to step up working capital loans up to ₹10,000 to street vendors, who have taken the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent lockdowns. Given the fact that the livelihood of street vendors has been adversely affected in the two waves of the pandemic, the central bank is keen that Banks mount a larger outreach under the PM Street Vendor’s AtmaNirbhar Nidhi (PM SVANidhi) scheme.

As on June 14, 2021, lenders (including Banks, non-banking finance companies, and microfinance institutions) received a total of 42,27,999 applications under the PM SVANidhi scheme, which was launched last year.

However, the ratio of the number of loans sanctioned and disbursed as a percentage of the total applications was only 58 per cent, as per Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) data. The ratio of the number of loans disbursed to loans sanctioned stood at 84.41 per cent. As a result, total loans approved and disbursed by lenders stood at ₹2,457.85 crore and ₹2,059.46 crore, respectively.

Conclusion: Microfinance in India plays a major role in the overall progress of society. It acts as an anti-poverty vaccine for the people living at the economic bottom of pyramid. It aims at assisting communities of the economically excluded to achieve greater level of asset creation and income security at the household and community level.