Largely people believe that only public limited companies or conglomerates and established companies, with many shareholders need to be concerned about corporate governance. They feel that these companies can benefit from implementing corporate governance practices; whereas, the reality is that all companies – big small, micro, private and public, start-ups, early stage (new) or established (old) compete in an environment where good governance is a business imperative. One size doesn’t fit all, but right-sized governance practices will positively impact the performance and long-term viability of every company.

Corporate governance is a tricky topic that board members and senior management must constantly revisit and improve. The business environment sometimes experiences recession and at times a boom. Increased fraudulent behaviours by business owners pull down citizen’s faith in businesses. There are some common myths about corporate governance which need illumination.

What are the common myths about corporate governance?

Myth 1: Corporate Governance is theoretical term.

This myth that corporate governance “doesn’t apply” comes from a view that it’s only theoretical and doesn’t impact the bottom line or performance. Also a lot of people believe that it is costly to implement it and it evolves bureaucratic practices when it comes to decision making. Some feel that it cannot be tailored to a company’s size and stage of development.

Reality: In reality, all companies (with or without) corporate governance compete in an environment where good governance is a business imperative in relation to things like raising capital, obtaining loans, attracting and maintaining talented and qualified people, meeting the demands and expectations of shareholders and expansion of firms.

Myth 2: Corporate governance does not have a single accepted definition, therefore it is vague idea.

Reality: Broadly, the term describes the processes, practices and structures through which a company manages its business and affairs and works to meet its financial, operational and strategic objectives and achieve long-term sustainability. It is generally a matter of law based on corporate legislation, securities laws and policies, and decisions of the courts and securities regulators. Directors owe a duty of loyalty to the companies they serve, and have a fiduciary duty to act honestly, in good faith and in the company’s best interests. Corporate governance is also shaped by other sources, like stock exchanges, the media, shareholders NGOs and interest groups. Corporate governance practices help directors meet their duties and the expectations of them.

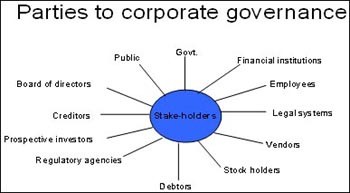

The objectives of corporate governance are to promote strong, viable competitive corporations accountable to stakeholders. There is no one particular design which fits every company, and there is no uniform, comprehensive set of policies or practices. The practices of corporate governance depend on several factors: the nature of the business, firm’s size, its lifecycle stage, how well the firm is expanded, availability of resources, shareholder expectations and its legal and regulatory requirements.

People who believe in corporate governance say that there is a direct connection between good corporate governance practices and long-term shareholder value. Some of the key elements for corporate governance practices are: a strong board of directors, accountability, good management practices, tough internal controls, increased shareholder engagement, risk taking ability, manageable risks and effectively monitored and measured performance.

Myth 3: One cannot expect a Return on Investment in Corporate Governance

Reality: Some companies view investment in corporate governance as a mandatory expenditure, whereas, few realize that it gives significant returns—directly and indirectly. In Asia and Latin America, for example, institutional investors pay on an average 22% premium for companies showing improvements in governance because they get better returns from improved stock performance. Companies with good governance also receive better credit ratings, which in turn help them get better interest rates, better supplier terms and improved working capital. Better governed firms do better than peers.

Companies must not view investment in governance as a necessary evil, but as an opportunity to mitigate risk, improve the brand and generate returns. CFOs and legal officers should measure and use return on investment in governance to obtain the support of the board for further improving the governance framework. Progressive organizations have corporate governance codes and conducts online; stakeholders can visit the websites and interact with the organizations.

Myth 4: Training Staff in ethical conduct can create a culture of good governance

Reality: Most firms will prove ineffective in establishing a culture of ethics. The amount spent on training the employees in ethical behaviour and their understanding differs. The percentage of employees completing training, does not measure whether employees are  behaving more ethically. Moreover, high-sounding principles in standardized governance training hold little meaning for employees and are rarely applied. Individuals have their core moral standards, which is difficult to be altered.

behaving more ethically. Moreover, high-sounding principles in standardized governance training hold little meaning for employees and are rarely applied. Individuals have their core moral standards, which is difficult to be altered.

Practically, the training modules must be tailored for each employee segment based on their work. Training should be scenario-based, describing ethical conduct in real-life situations.

Myth 5: Regulatory compliance ensures good governance

Reality: Legislation can never account for a large proportion of corporate frauds; firms which want to get into frauds can find loopholes in system. Firms cannot rely on compliance to create ethical behavior. A lot of large scale corporate frauds are committed by employees at firms that comply with all necessary regulations. For example, Satyam Computer Services Ltd, saw its employees commit India’s largest ever corporate fraud, was compliant with Indian law and International Financial Reporting Standards financial disclosures.

Firms should not wait for laws to become stricter and then change the governance standards in the daily working. Instead, firms must ensure that they comply with best practices and highest possible standards, which helps the firms stay ahead of legislative change and also puts senior managers in a stronger position to argue for reforms that benefit companies as well as society.

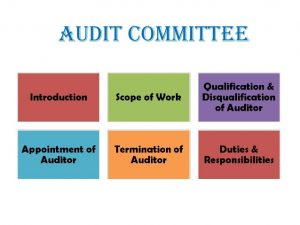

Myth 6: Audit committees are the most important to reinforce corporate governance

Reality: While audit committees take the blame for lapses in governance, the reality is that boards often do not give the audit committee the right scope or support it with the right processes. Audit committees’ ineptness has little to do with their powers or the quality of the directors. Their focus is often diluted as committee  charters and responsibilities are rarely defined, and the group often becomes an owner of risks which he board of the firm does not want. This impedes oversight on governance and increases risks of frauds.

charters and responsibilities are rarely defined, and the group often becomes an owner of risks which he board of the firm does not want. This impedes oversight on governance and increases risks of frauds.

Firms which formalize the audit committee charter and conduct meetings and agendas at the beginning, and make those reports available to public build market confidence.

Myth 7: A strong fraud management system is the most important way to record misconduct

Reality: When firm establish fraud detection and controls systems, but do not take actions which are most important, it loses sense. Fraud managements are not enough to reduce misconduct. To build an effective governance framework, progressive companies create a culture of ‘speaking-up’ under which employees report misconduct without the fear of retaliation. It has been observed that when employees speak up (who are called whistleblowers), they are fired, or harassed by the top officials. According to a 2010 Association of Certified Fraud Examiners report, employee information was found crucial in clearing up 47% of fraud cases, which is more than all the other tools fraud management relies on. Organizations must reinforce the commitment to integrity with a strong ‘tone from the top’ and demonstration of organizational justice. A lot depends on the conduct of top management people’s behaviour.