As we grow up in age, our world changes. We become busy in activities related to our career, profession, family, children, parenting, maintaining our social status etc, etc. Our responsibilities pile up and in the journey we tend to forget our friends. Our best friends become our distant friends and our distant friends become a faint memory. Life moves on while our memories of our friends slowly begin to fade away. Reminiscing over past days becomes painful. But, we all crave for friends……and social media recognizes this innate craving of us and therefore the concept of virtual friendship has caught up.

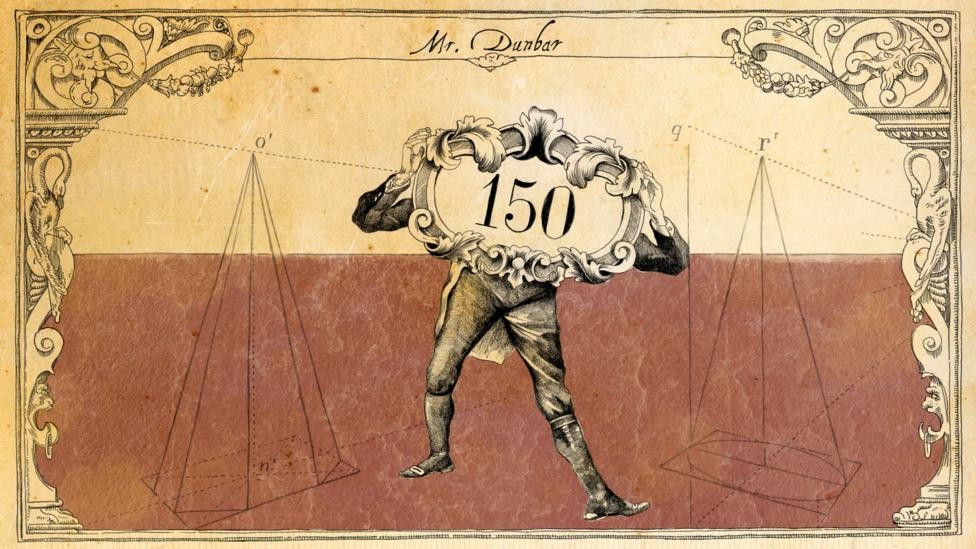

A bigger world may mean a world with more opportunities, but it goes without saying that profitable gain is not the only standard by which to judge a potential relationship. Dunbar’s number is a suggested cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships in which an individual knows who each person is and how each person relates to every other person. Robin Dunbar is a British anthropologist, who found a correlation between primate brain size (for a given body size, have brains 5 to 10 times as large as the formula predicts) and average social group size. By using the average human brain size and extrapolating from the results of primates, he proposed that humans can comfortably maintain 150 stable relationships. Dunbar explained it informally as “the number of people you would not feel embarrassed about joining uninvited for a drink if you happened to bump into them in a bar.” So, Dunbar’s Number is based on an idea that 150 is the number of individuals with whom any person can maintain stable relationships.

Dunbar and his team also have performed research on Facebook, using factors like the number of groups in common and private messages sent to map the number of ties against the strength of those ties. When people have more than 150 friends on Facebook or 150 followers on Twitter, Dunbar argues, these represent the normal outer layer of contacts or the low-stake connections: be it 500, 1000 or 1500. For most people, intimacy may just not be possible beyond 150 connections. In his opinion, various digital media are really just providing us with another mechanism for contacting acquaintances.

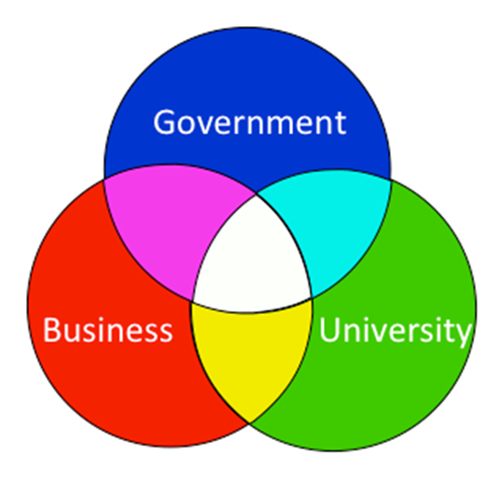

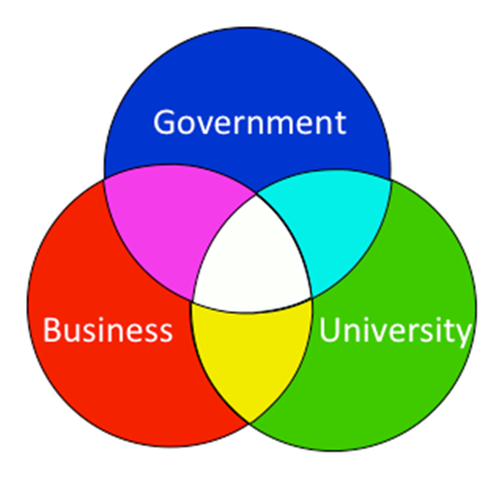

Dunbar says there is a consistent pattern, and it scales roughly by a factor of 3 each time: 5 Intimates, 15 Good Friends, 50 Close Friends, 150 Friends. He supposes that the numbers continue beyond that – 500 acquaintances and 1500 people who you could put a name to a face.

Factually, Dunbar’s own research suggests generational differences in this regard. Those aged 18–24 have larger online networks than those aged 55 and above. And the dominance of physical contact in the social brain hypothesis may apply less to young people who have never known life without the Internet, for whom digital relationships may be just as meaningful as analogue ones.

Plus, online groups like 100s under 100 aren’t going to last forever; initially envisioned group would dissolve within a few years. Without the pressure for longevity, ideal community size may be less relevant. It makes sense that there are a finite number of friends most individuals can have. What’s less clear is whether that capacity is being expanded, or constricted, by the ever-shifting ways people interact online.

Isn’t it hard to cry on a virtual shoulder? Can you compare an online conversation to personal meeting? Does that give that closeness feeling? Virtual friendship does not last, it’s literally fragile says Dunbar. Even the possibility of anonymity online doesn’t seem to be substantially different to the offline world to Dunbar. He compares anonymous internet interactions to the use of confessionals in the Catholic Church. It isn’t a close relationship, but it is one that recognises the benefits of confidentiality among quasi-strangers.

Weak ties, on the other hand, are not generally part of the same world. You find more of cheats on social media. Strong ties make the world smaller; weak ties make it bigger.

And, as you grow older, your maturity and experience of life gives you a chance to evaluate, sieve and settle for true friends who you know will stay no matter what, no matter how circumstances change. These true friends love you for who you are, not for what you have. And you love them in the same way. Stay with friends who prioritize you and love you for what you are. You enjoy their company and they enjoy yours. Your conversations are great; you’ll laugh together, share drinks and eat together. It’s really hard to find true friends like these so maybe there are just two, three or maybe four, if you are lucky. It’s never an entire gang. And that’s the way I’m sure we like it because it take less effort to maintain true friends than ten on-and-off buddies.

A close friend is someone you rely on and can trust, but a best friend is a person with whom you share everything. The key distinction is that level of friendship shared by two best friends is greater than two close friends. He or she is always there in difficult times and cares for the friend. Whether one or two or five friends, spending time with friends is fun. It yields a multitude of long-term physical and emotional health benefits. Studies show that healthy relationships make aging more enjoyable; it lessens grief, and provide camaraderie to help you reach personal goals, among other things.