Handle Product Proliferation with Care

Branding is a complex process it is tough job for any marketer to personify a product or a service into an image that is either liked or not does not be liked. Marketers keep juggling with branding strategies which at times become a hit. To introduce one new product and build a brand out of it, is itself a very intimidating task and to have a plethora of brands in the portfolio can suffocate the basket of products. This concept of launching and managing a plethora of brands by one company is considered as Brand Proliferation.

Brand proliferation is the opposite of brand extension. While in brand extension, new items are added using an existing brand name and several products are offered under the same brand name, in brand proliferation, more items are added to the product line with different brand names. In other words, the firm has several brands in the same product line or product category. It means that the list of independent brands increases. For instance, Unilever has more than 25 brands of ice creams and P&G has more than a dozen brands of detergents. This produces diversity for the firm as it is able to capture its sizable portion into various market segment. However, it can also lead to money spinning because of too many products, efforts and economic resources being wasted. The consumers get confused and they make mistakes while purchasing the products.

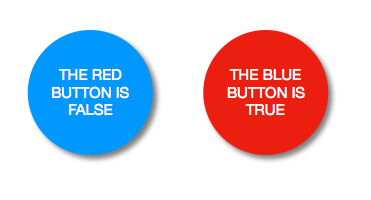

Each brand requires a different treatment, each brand is a unique identity, and each brand needs a unique handling; the very dynamism of product proliferation makes it hard to manage the brand. Complexities multiply by an ever-changing landscape of customers who demand and companies’ attempts to meet that demand with formation of products and more product variations. Brand proliferation also leads to brand cannibalization; each brand eating into market share of another product from the same basket.

ITC’s soap portfolio consists of a product line with Essenza Di Wills at the top end, followed by Fiama Di Wills in premium segment, Vivel in mid-segment and Superia at the entry level. ITC seems to have segmented the market fittingly and has different products to cater to different segments. Moreover, Vivel is targeting young consumers who are ready to flirt with new brands. The large array of products in the toilet soap category offers consumers access to some of the best-in-class products in different segments with vibrant attractive pricing and packaging. Brand proliferation can help expand the company’s market share in a particular category. It can also increase the company’s clout at the retail level by offering variety. New brands also generate enthusiasm of the sales team of the company at the same time, but all of this also creates many pitfalls in the process. More brands from a company’s product basket increases competition in the market. The main advantage of proliferation is that the company’s presence is felt overall in the market.

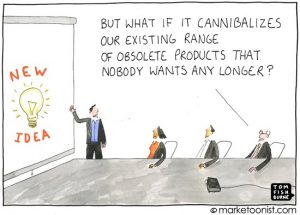

On the negative side, when a firm introduces a number of brands in the same product line with an amount of parity among them, the danger of cannibalization is high; the share of individual brands can come down because of its own sibling brands. Another disadvantage is that the company may dissipate its resources over several brands, which may not guarantee proportionate returns, nurturing just a few brands to a highly profitable level often proves to be a wiser option.

Having brands with distinctive positioning is, strategically, the best way of minimizing cannibalization. If different brands are designed to deliver different benefits to different segments of markets, it can restrict competition among brands. To avoid cannibalization completely is often impossible. It is not essential either, but one has to be sure whether a net incremental benefit that justifies the additional cost and complexity accrues by adding one more brand. It’s differentiating for the sake of differentiating and can retort back when not sensibly used.

I am awe of Maruti Suzuki the way it handles it product portfolio. As of January 2016, Maruti Suzuki has about 47% of the Indian passenger car market. Maruti Suzuki manufactures and sells its popular cars to each segment such small size, mid-size, SUV, Sedan, Saloon and Hatchback. It has a car for each segment – the Alto, Swift, Zen, Celerio, Wagon R, Swift, DZire, SX4, Omni etc. Maruti Suzuki has 146 cars models available in India out of which 85 are hatchbacks, 26 are sedans, 14 are SUVs and 19 are MUVs/MPVs. Maruti Suzuki has total of 85 petrol cars, 50 diesel cars and 11 CNG cars. There are 21 automatic cars and 125 manual transmission cars to select from. Alto 800 is the most economical car and the most expensive model is S Cross. Vitara Brezza is the latest car by Maruti Suzuki launched on 8th March, 2016. Maruti Suzuki is the apt example of how a good brand proliferation strategy strikes a fine balance so that too many brands do not result in brand cannibalization and erosion of profits.

Companies in their struggle to compete with other brands and the compulsions of growth often do not have kind of definite time at their disposal and time is the essence. They find takeover, acquisition and buyout of ongoing brands as an easy way out. For example, while entering India, Pepsi wanted to enlarge its brand portfolio and to ensure it without much gestation it went in for out of some ongoing brands. Pepsi acquired the 105 year old Duke’s and gained two powerful brands, Duke’s Soda and Mangola overnight. It gained a strong position in the Mumbai market which has dominated traditionally by Duke in the relevant categories. Similarly, Godrej acquired Traselecta, the company which actually revolutionized the Indian home insecticides market with many successful brands like Good Knight, Hit, Jet and Banish, it was essentially a case of acquisition of brands. The acquisition was part of Godrej’s long term strategy to become a substantial player in the growing home clean product market. It needed brands in the category.

It is worth noting, that most organizations do not go into depth of examining their brand portfolios from time to time: this examination is essential to check if they are prone to sell too many brands, identify the weaker brands, and discontinue the loss making brands or the unprofitable ones. When organizations tend to ignore loss-making brands and merge them with healthy brands instead of selling them off, or drop them they choke the healthy brands. Furthermore, the startling truth is that most brands don’t make money for companies. The 80-20 thumb rule is a reality that organizations make 80% profits from 20% of their products. From a small number of brands. Unilever had 1,600 brands in its portfolio in 1999, its business spread over in some 150 countries. More than 90% of its profits came from 400 brands. Most of the other 1,200 brands made losses or they earned marginal profits. Another example is of Nestlé – in 1996 it marketed more than 8,000 brands in 190 countries. About 55 of them were global brands, 140-odd were regional brands, and the remaining 7,800 or so were local brands. The bulk of the company’s profits came from around 200 brands, or 2.5% of the portfolio.

If only corporations realize that if they slot several brands into the same category, they incur hidden costs because multibrand strategies and they give partial treatment to healthier brands.