The cobra effect occurs when an adopted strategy or solution to a problem makes the problem worse because of unseen consequences. The term is used to illustrate the causes of incorrect stimulus in economy and politics. The expression originates from an incident which took place when the British ruled India. The British government was disturbed about the number of poisonous cobra snakes in Delhi. The government therefore offered a reward for every dead cobra. Initially this was a successful strategy as large numbers of snakes were killed for the reward. Eventually, however, enterprising people began to breed cobras for the income! When the government learnt it, the reward program was scrapped. This decision of government caused havoc as the cobra breeders set the now-worthless snakes free. As a result, the wild cobra population increased further.

America’s war on drugs began in 1971, when Richard Nixon declared drug abuse as “public enemy number one.” He intended to suppress the illegal drug trade, the consequence turned bitter. It created a permanent underclass consisting of drug criminals – sort of a lobby of federal offenders; the drug peddler’s voting rights are withdrawn; they are refused education and employment too. The consequence of this action is it has fueled cartel of violence in Mexican countries. The crux of this story is that bin Laden’s money gave him prominence on the Afghan scene and he used the Mexican underclass to turn his fighters against the US, bringing America into the war in the Middle East.

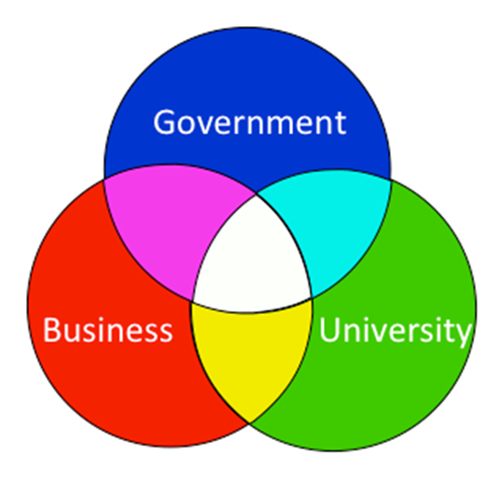

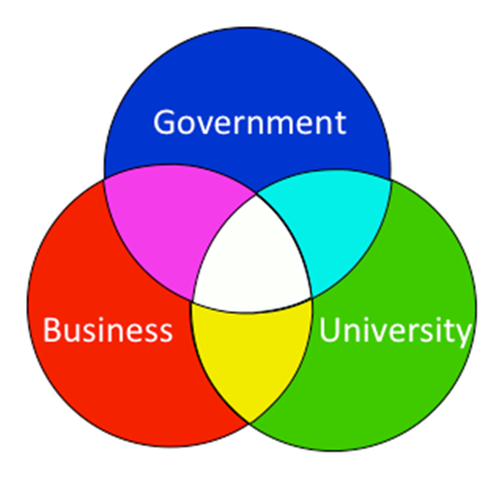

Let’s not forget that the world is highly interlinked; governments and business organizations must realize that their strategies and actions have multiple outcomes. When an action is taken, the intended outcome might occur with a number of unexpected outcomes. What becomes worrisome is that those unexpected outcomes can be dangerous. While planning and organizing strategies organizations need to think of outcomes counter-intuitively. There is something called policy-surprises. The government officials and business managers must try to improve their intuitiveness in regards to after effects in complex socio-ecological systems.

Delhi CM Kejriwal used the model of Mexico City to fight air pollution. In the late 1980s in Mexico City, which was at the time suffering from extreme air pollution caused by cars driven by its 18 million residents, the city government responded with Hoy No Circula, a law designed to reduce car pollution by removing 20 percent of the cars which were determined by the last digits of license plates from the roads every day during the winter when air pollution. Oddly, though, removing those cars from the roads did not improve air quality in Mexico City. In fact, it made it worst.

Some people carpooled or took public transportation, which was the actual intent of the law. Others, however, took taxis, and the average taxi at the time gave off more pollution than the average car. But, group of people ended up undermining the law’s intent more significantly. That group bought second cars, which of course came with different license plate numbers, and drove those cars on the days of week they were prohibited from driving their regular cars. What kind of cars did they buy? The cheapest running vehicles – those which emitted more pollution into the city at a rate far higher than the cars they were not permitted to drive. The people released their cobras – in this case the cars into the streets.

When policy makers don’t look at after effects an endless whirl of

consequences gets created; the

consequences have consequences, and the consequences of those consequences have

consequences, this goes on. It gets very complicated. For example, if hospitals

are asked to publish their mortality rate, to reduce the same they turn away

terminally ill patients.

It’s very important to understand cause-and-effect relations in complex systems.

We need to look beyond linear thinking. In particular, we need to understand

the concept of feedback and appreciate the dominant role it plays.

Another instance makes cobra effect more clear. Way back in 1976, In Venezuela when government decided to nationalize its oil industry, the intent was to keep oil profits in the country. But when the government takes over a once-private industry, the profit incentive to maintain physical capital is lost, and physical capital depreciates. The deterioration plays out over a decade or so, and that’s what made it appear at least for a while. Unlike everywhere, Venezuela’s socialism was working. But as the oil industry’s physical capital broke down, oil production fell. Coincidentally, it was around this time that oil prices fell and the ultimate unintended consequence of Venezuela’s nationalizing its oil industry went berserk.

As oil revenues and production plummeted, Venezuela’s government acted the way governments inevitably do when revenues disappear. It borrowed and taxed as much as it could, and then it started printing money. The printing led to the unintended consequence of inflation and then prices rose so high that people could no longer afford food. To respond to this unintended consequence, the government imposed price controls on food. But this created a new unintended consequence wherein farmers could no longer afford to grow food. And so the farmers stopped growing food. Finally, the government forced people to work on farms in order to assure food production. Thus ultimate unintended consequence of Venezuela’s nationalizing its oil industry resulted into slavery.

Cobra Effect creates unintended consequences everywhere. Seat belt and airbag law makes the pedestrian and cyclist unsafe as the drivers become less cautious. Essentially the Cobra Effect tells that when policy makers make policies based on linear thinking using logic, it requires intuitiveness in regards to consequences.