Gautam Thapar led Avanta Group’s Jhabua

thermal power plant is declared as stressed project undergoing resolution as

per the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). It has

faced land acquisition and funding issues leading to time and cost overruns.

NTPC and Adani group have bid in which NTPC has bid ₹ 1,900-crore offer that was two and-a-half times more than the rival bid of

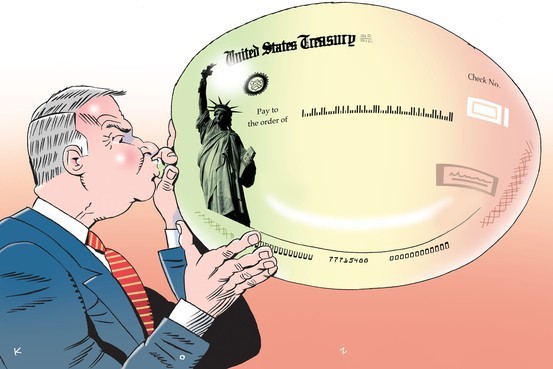

Adani. A typical NPA like this requires a mediator like a bad bank which could

play a great role because NTPC’s money goes from the government’s fund.

Bhushan Steel, the largest manufacturer of auto-grade steel in India, has a loan default of ₹ 44,478 crore. The State Bank of India, the lead bank of the consortium of lenders, had moved the NCLT for recovery of its loan. Sajjan Jindal-led JSW Steel showed immense interest in buying out Bhushan Steel. But, finally Tata Steel has acquired Bhushan Steel (BSL) through its wholly-owned subsidiary Bamnipal Steel Ltd (BNL) through a resolution under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). Tata Steel has taken a controlling stake of 72.65% in BSL and paid the admitted corporate insolvency costs and employee dues.

Lanco Infratech, once listed among fastest growing in the world, has a loan default of ₹ 44,364 crore. IDBI has already initiated the process under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code against company’s loan defaults. Vedanta and a Hyderbad-based investment company have bid for Lanco Infratech.

The above examples and another big list of NPAs have led to a news item of 12th June 2020 in Economic Times which says that State Bank of India and the Indian Banks’ Association have once again revived the proposal for a bad bank which is not just desirable but is most vital. At the moment, India’s most banks are deep into venturing NPAs and to start lending again, to fuel growth, the banking sector needs dynamic strategies. India needs not just any bad bank, but a bad bank jointly owned by the banks themselves. Nonetheless, the Chief Economic Advisor, K Subramanian, has expressed himself not in favour, on the ground that there already are 28 asset reconstruction companies in operation and banks have been unable to sell their bad loans to these entities. Under such circumstances, what nature of ownership could a new bad bank play, and is it viable?

What is a bad bank? To begin with, it is a bank which takes over, that is it buys at a discount, the non-performing loans of banks and then resolves the assets over time, say over five years, leaving the banks that sell off their bad loans and clean up their books. This kind of clarity on their finances helps them in making a fresh start, to raise capital with better ratings and on better terms and to make loans. When a bank is already loaded with a high proportion of bad loans, its appetite for making fresh loans becomes depressing.

It is all the more imperative to tackle post-Covid recovery because until banks are free of their bad-loan burden. And the only way they can do this fast is to unburden their bad loans by selling them off to a bad bank.

Why can’t the banks sell their bad loans to the existing asset reconstruction companies, set up to buy bad loans and resolve them? Bad loans have to be sold at a discount. If a loan of ₹ 1,000 crore has turned non-performing, it cannot be palmed off for ₹ 1,000 crore. The buyer will buy it for say, ₹ 520 crore, or ₹ 600 crore, or even ₹ 400 crore, depending on the probability of realising the money from selling off the assets with which the loan has been secured. Banks are dead scared of accepting a sharp discount, because they might be accused of causing a loss to the bank, and indirectly, to the exchequer, in the case of public sector banks. The Private Sector Banks are no different than the PSBs disturbed private sector lender Yes Bank is in discussions with several asset reconstruction companies (ARCs) to sell off bad loans worth ₹ 32,344 crore. It has appointed EY as an advisor for the bids, Business Standard reported.

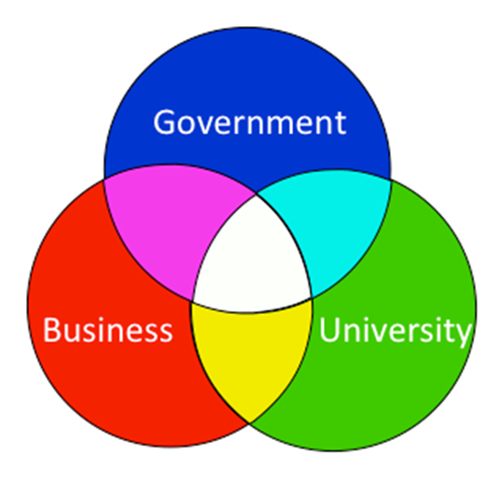

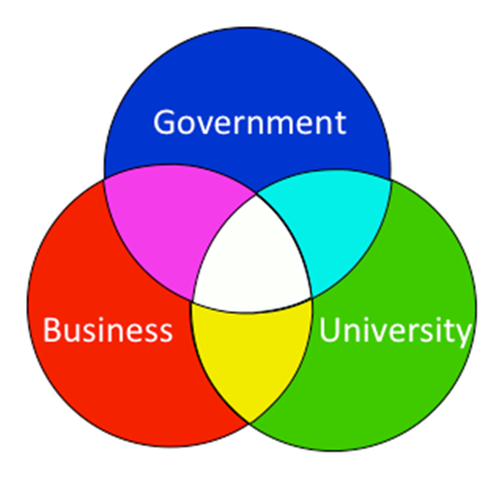

The key to the success of a bad bank is its ownership. It should be owned by all the public sector banks, which account for the bulk of non-performing assets on banks’ books, and by private sector bank that want to join in. Their respective shares of ownership can be their share in the total bad loan portfolio. The advantage of having a bad bank owned by the banks collectively is that when the assets underlying a bad loan is resolved, the profits will accrue to the owners, that is, the banks themselves. This would make the loss they book on selling the non-performing assets at a discount more palatable. The better-quality assets would sell at a premium; say power assets that turned non-performing just because a state government went back on its power purchase agreement.

The first bad bank in world experiment was a complete success. In 1988, Mellon Bank of Pittsburgh convinced the Federal to let it set up another bank that would take no deposits but just buy Mellon’s bad loans and resolve them. Mellon gave the bank named Grant Street National Bank, some equity and some preference shares. The rest of the money needed to buy Mellon’s $1.4 billion worth of bad loans at a discount of 53% was raised by issuing short-term bonds: collateralised loan obligations. Drexel Burnham Lambert, the investment bank that specialised in issuing high-yield bonds under junk bond king Michael Milken securitised Grant Street’s assets. There were two tranches of bonds, senior and junior. The senior tranche (portion of money) received investment grade rating while the junior tranche had junk rating and offered a much higher yield. Reportedly, the whiz kids at Drexel dubbed the junior tranche bonds CLOWNS, or Collateralised Loan Obligations worth Nothing Securities. But all securities were paid in full. And Grant Street was wound up.

Mellon hired Arthur Andersen & Co to price the loans for sale to Grant Street. The price arrived at by Arthur Andersen was reviewed by Kenneth Leventhal & Co, an accounting firm with a special grip on real estate, which helped Donald Trump out during his real estate company’s bad times. Such arms-length pricing would be a key to the success of the proposed bad bank in India, too. And if the sale is to a company owned by the banks themselves, and if it has the mandate not just to sell on an ‘as is’ basis but also to run/complete the asset and then sell it off, bankers would have much less to worry than when selling bad loans to private ARCs. And when a bad bank will play a central role, private ARCs would be able to compete with the bad bank to buy stressed assets and pricing would become competitive.

I conclude – bad bank experiments have worked well around the world. It will work well in India too because it will reduce the bankers’ fear of being harassed for selling their bad loans cheap can be addressed. In fact, it’s need of the hour in India.