Advertisements and the brand ambassadors are marketing or cheating??

A Brand Ambassador is someone who, at the most elementary level, symbolizes a brand in a positive way; he/she embodies a brand. The brand ambassador communicates the message of a company to consumers or people who would be interested in buying the company’s brand after learning about it. Thus, BA puts a human face on the multi-million dollar corporations because consumers associate with them more effectively.

The affinity consumers have for certain celebrities can greatly influence their purchase decisions. People perhaps feel that, “If the product is good enough for her, its good enough for me.” This philosophy is often the force behind advertisements for makeup, skin creams, lingerie, banks, eatables, beverages and attire. The brand ambassadors infuse confidence in the consumers to use a product/service. Essentially, the celebrity’s testimonial adds instant reliability to a small or big brand.

That’s why brand ambassador is a part of the company’s marketing and sales team. Celebrities endorse for products in lieu of heavy money. Therefore, they automatically become responsible if the brand turns out to be spurious/bogus/contaminated. It’s simple, before endorsing a product it’s their responsibility to check the credibility of a product/service. In the recent Maggi Noodle’s fiasco, the Uttar Pradesh Food and Drug Administration’s decision to recall packets of Maggi Noodles for reportedly having monosodium glutamate and lead more than permissible limits, film star Madhuri Dixit, who endorsesMaggi’s brand of ‘nutritious’ oats noodles is in trouble. The Haridwar FDA has issued her a notice seeking an explanation as to how the noodles are nutritious, and on what the basis Nestlé is making such a claim. If she fails to respond within a fortnight, a case could be filed against her, according to officials of the FDA.

Can ambassadors simply shrug off their responsibilities when the brands endorsed by them turn out unauthentic? Misrepresentation of products, especially in the food sector, is a serious issue, and not as silly as many would like to believe. In February 2014, last year, the Central Consumer Protection Council, under the leadership of former Union Food Minister KV Thomas, decided unanimously to propose laws to hold celebrities endorsing products also liable in cases of misleading advertisements. The rationale behind this decision of the CPCC was that celebrities had considerable influence over consumer choice, and that there must be some form of liability for the endorsements being made.

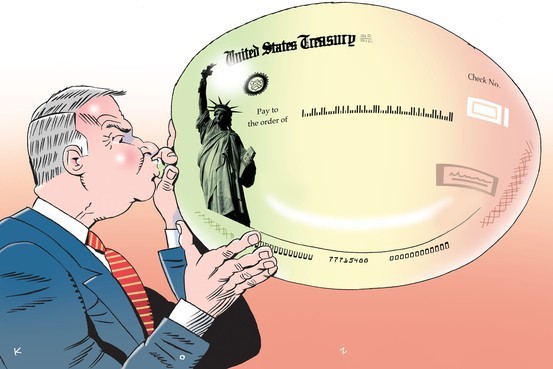

In US, Kellogg’s popular Rice Krispies cereal had a crisis in 2010 when it was accused of misleading consumers about its immunity boosting properties. The Federal Trade Commission ordered Kellogg to halt all advertising that claimed that the cereal improved a child’s immunity with “25 percent Daily Value of Antioxidants and Nutrients — Vitamins A, B, C and E stating the claims were “dubious.” Ironically, just a year prior, the company settled with the FTC over charges that its Frosted Mini-wheats cereal didn’t live up to its ads. The campaign claimed that the cereal improved kids’ attentiveness by nearly 20%, and was shot down when the FTC found out that the clinical studies showed that only 1-in-9 kids had that kind of improvement and half the kids weren’t affected at all. Now, we just cannot imagine this kind of strictness and vigil in the Indian administration. Our laws are indistinct and lack spirit to take up firm steps.

There is a notion that brand ambassadors can’t generally be tamed. The ad agencies do speak in favor of their models. When the going is good, everyone wants to be party to the success, but, when the going gets bad you can test the actuality of people. The celebrities behave larger than life. They should be held guilty for false advertisements because they exploit their fan following and their popularity. The fans revere them so much; they follow their personal lives and their styles to no end. Tiger Woods was a brand ambassador for Gatorade, Gillette, Accenture, AT&T, Gold Digest and Tag Heuer. After his plentiful extramarital affairs were revealed, the majority of these brands discontinued him as they found it difficult to continue him as their brand ambassador.

In India in 2012, actress Genelia D’Souza was summoned by court for allegedly making false promises through ads and brochures for a real estate company in Hyderabad. Andhra Pradesh High Court demanded her explanation as brand ambassador for a project called ‘Anjaniputra’ located close to Hyderabad Deccan when the project seems to have gone bust. This is the latest in how society and the laws in India are dealing with the extremely doubtful advertisements. It is a matter of time before similar questions are raised by other consumers who are swayed into investing in products or services, by fraudulent advertisements endorsed by celebrities who are supposed to also be role models.

The Home Trade scam of 2002 had the celebrity endorsement of three big celebrities, Sachin Tendulkar, Hrithik Roshan and Shah Rukh Khan. Having created not a single product, the company made away with thousands of crore rupees of investor money, and celebrity-endorsed brand building was a crucial part of their operation. Activists have also been speaking out against ads for sauna-belts, medicines, Hanuman-chalisa yantra and gem-stones on TV screens.

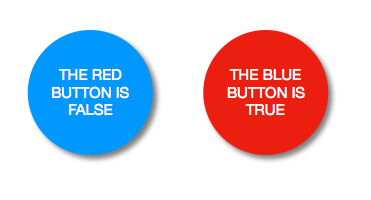

How can celebrities vouch for the authenticity and effectiveness of that product with great confidence without checking them? Like with politicians, an advertisement and the celebrities involved in it can simply be voted out. They can be thrown out in disgrace. This message is clear; the company and ad agencies cannot work on the premise that the consumers are fools. They better learn to respect their constituency, i.e. the consumers.

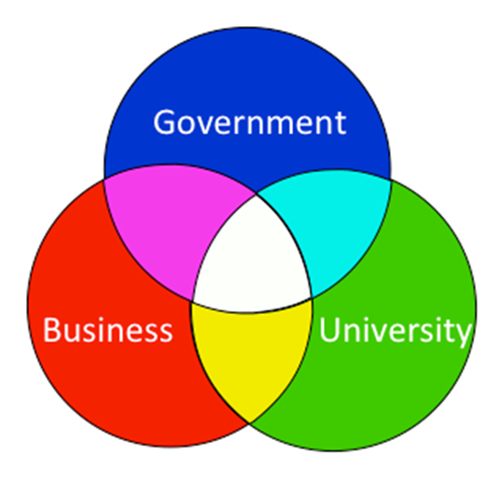

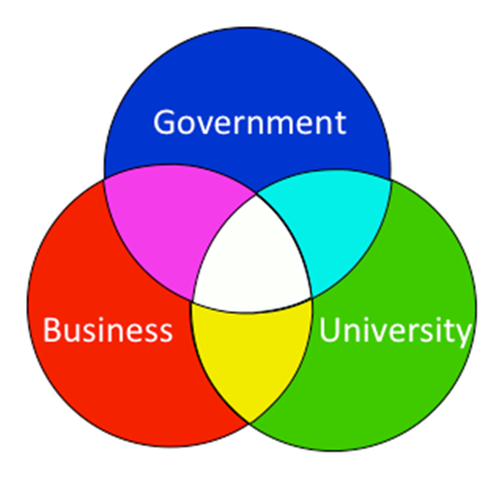

Due diligence should be exercised before making of an ad. All stakeholders must share their responsibilities. The three stake-holders in ad making are advertiser, advertising agencies and the media. Let’s understand this straight: in advertising, there’s a big difference between pushing the truth and making false claims. Most of us have some or the other time in our life been victims of false advertising. Are we going to take it lying low or question the companies to change their marketing policies? Can we allow the companies to continue to prioritize profits over the consumers?

In progressive countries like America and Europe companies need to face harsh penalties. Companies are made to pay up the consumers for cheating them.

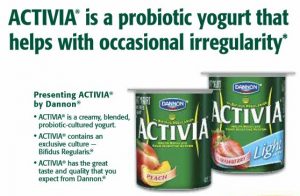

Dannon’s popular Activia brand yogurt lured consumers into paying more for its purported nutritional benefits when it was actually pretty much the same as every other kind of yogurt.

In Canada and America law suits were filed against Dannon for falsely touting the “clinically” and “scientifically” proven nutritional benefits of the product. In spite of the company got a famous spokesperson, Jamie Lee Curtis, for the supposed digestion-regulator, some customers didn’t buy it. Do you know that a class action settlement forced Dannon to pay up to $45 million in damages to the consumers? The company also had to limit its health claims on its products strictly to factual ones.

In another case, hundreds of car owners were extremely disappointed to find out that Hyundai and Kia Motors overstated the horsepower in some of their vehicles. In 2001, the Korean Ministry of Construction and Transportation uncovered the parody, which for some models was as much as 9.6 percent more horsepower than the cars actually had. A class action lawsuit in southern California claimed the companies were able to sell more cars and charged more per vehicle because of the false claims. In the end, the auto powerhouses had to pay customers; the settlement estimated to be between $75 million and $125 million.

In India, to protect rights of consumers the process of filing complaint and finding resolution needs a drastic improvement. Strict guidelines should be made and law suits must be resolved in minimum a week’s time. Then, we might find respite from getting cheated recurrently by companies, their advertisements and savvy brand ambassadors.