For all managers criticism is part and parcel of life

Decision making is a part and parcel of our daily life. For managers its part and parcel from moment to moment; their each action and decision is observed by their bosses, peers, assistants because their decisions are critical to the organization’s growth. Some decisions are small, some are big, some are good, some are not so good… but still decision making is vital. Some decisions can affect somebody’s life, livelihood, and well-being. Inevitably, sometimes the manager makes mistakes along the way. Therefore, decision making is scary reality that requires great understanding of complexities; thus, the manager’s maturity, intelligence, responsibility, and his people skill matters. It’s been seen people with the best information and intentions are sometimes hopelessly flawed.

Decision making is a part and parcel of our daily life. For managers its part and parcel from moment to moment; their each action and decision is observed by their bosses, peers, assistants because their decisions are critical to the organization’s growth. Some decisions are small, some are big, some are good, some are not so good… but still decision making is vital. Some decisions can affect somebody’s life, livelihood, and well-being. Inevitably, sometimes the manager makes mistakes along the way. Therefore, decision making is scary reality that requires great understanding of complexities; thus, the manager’s maturity, intelligence, responsibility, and his people skill matters. It’s been seen people with the best information and intentions are sometimes hopelessly flawed.

Managers can make mistakes and sometimes they might be grave mistakes. Daimler led the merger of Chrysler and Daimler against daunting internal opposition, nine years later, Daimler was forced to virtually give Chrysler away in a private equity deal.

Steve Russell, chief executive of Boots, the UK drugstore chain, launched a health care strategy designed to differentiate the stores from competitors and grow through new health care services such as dentistry. It turned out, though, that Boots managers did not have the skills needed to succeed in health care services, and many of these markets offered little profit potential. The strategy contributed to Russell’s early departure from the top job. Sometimes excitement needs to be resisted.

Brigadier General Matthew Broderick, chief of the Homeland Security Operations Centre, who was responsible for alerting President Bush and other senior government officials if Hurricane Katrina breached the levees in New Orleans, went home on Monday, August 29, 2005, after reporting that they seemed to be holding, despite multiple reports of breaches.

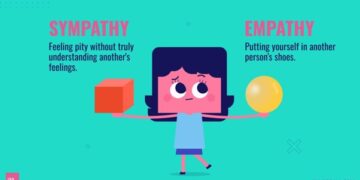

All these executives were highly qualified for their jobs, and yet they made decisions that soon seemed obviously wrong. It happens at times, we all make decisions which can go drastically wrong. We make mistakes in the planning process, in designing or strategising we miss the threads somewhere. Flawed decisions start with errors of judgment made by powerful individuals. We depend primarily on two hardwired processes for decision making. Our brains assess what’s going on using pattern recognition, and we react to that information—or ignore it—because of emotional tags that are stored in our memories. Both of these processes are normally dependable; they are part of our evolutionary advantage. But in certain circumstances, both can let us down.

When an executive takes a big decision, he or she typically relies on the judgment of a team that has put together a proposal for a strategic course of action. After all, the team will have to look into the pros and cons much more deeply than the manager/executive has time to do. The common problem is, biases invariably creep into the team’s reasoning and often precariously distort its thinking. A team that has initially appreciated with a proposal, for instance, may subconsciously dismiss evidence that contradict its theories, give far too much weight to one piece of data, or make faulty comparisons to another business case.

When an executive takes a big decision, he or she typically relies on the judgment of a team that has put together a proposal for a strategic course of action. After all, the team will have to look into the pros and cons much more deeply than the manager/executive has time to do. The common problem is, biases invariably creep into the team’s reasoning and often precariously distort its thinking. A team that has initially appreciated with a proposal, for instance, may subconsciously dismiss evidence that contradict its theories, give far too much weight to one piece of data, or make faulty comparisons to another business case.

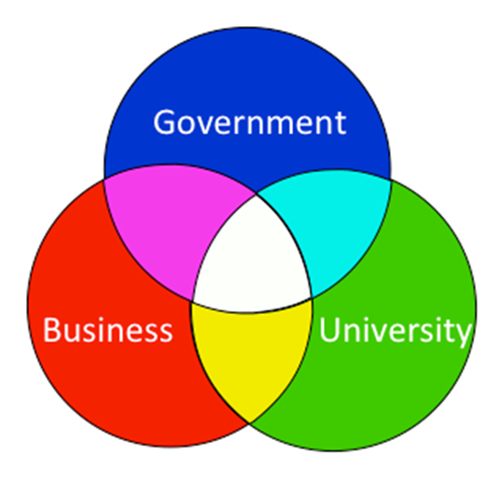

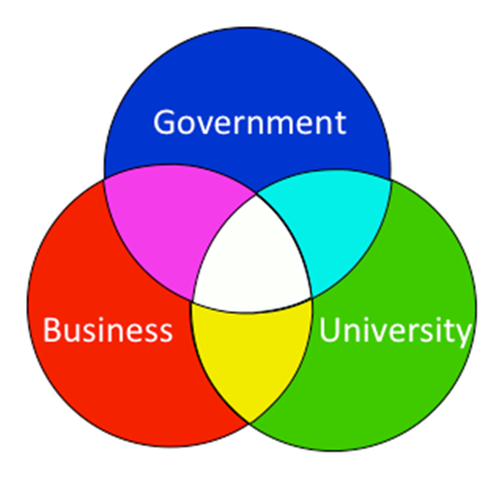

For one reason or another, someone will find a reason to project their insecurities, their negativity, and their fears onto the process of execution. Others in the team need to need to deal with it. We live in times of stifle change; shifting powers between government agencies, consumerism, globalization and maddening short product life cycles. Technology today is so short lived, emerging countries and changing economic landscapes, financial systems that are under severe pressure, new innovative companies that change market places.

Today’s leaders are dealing with an exponential change rate, and with information and communication channels that are easier accessible, faster and more widespread than ever before. Leaders are exposed to external influences and pressures that are less conventional and more quickly come and go. Leading change requires leaders to cope with this higher level of complexity. It also means that they, as part of their job, will almost inevitably face criticism in many occasions. Great leaders are aware of this and deal with criticism constructively. They see it as a normal part of their role and they approach it with an open mind. They have a fundamental and positive impact on the change, precisely because they deal with criticism effectively. They realise that execution is critical to success.

According to Jack Welch of GE boundary less behaviour and constantly searching for better ideas is the need of the hour for all managers. Here’s what he says about innovation: “If you’ve got a company that has a mentality inside that is filled with searching for a better idea every day, not just as a slogan but as a real concept, you will have innovation around you all the time.”

Lets except this fact – that as people we are biased in every single situation, there’s no such thing as objectivity. The truth about criticism is that it’s almost always in your head.

I think when managers mature they realise that when leading change, it is normal to encounter resistance. It is evidence that change is taking place. Criticism is just one of the ways in which resistance expresses itself. That doesn’t make it pleasant, but it is ‘normal’ in situations of change. Great leaders see criticism as an opportunity. They embrace it and use it to engage people, to create awareness for change, to facilitate dialogue. They use it as fuel for change. Not in a calculating way, but with an open mind and a willingness to change views and perspectives.

I think when managers mature they realise that when leading change, it is normal to encounter resistance. It is evidence that change is taking place. Criticism is just one of the ways in which resistance expresses itself. That doesn’t make it pleasant, but it is ‘normal’ in situations of change. Great leaders see criticism as an opportunity. They embrace it and use it to engage people, to create awareness for change, to facilitate dialogue. They use it as fuel for change. Not in a calculating way, but with an open mind and a willingness to change views and perspectives.

They make the complexities understand to others. Leaders have to deal with a great amount of change every day and are confronted with a higher level of complexity. More and more resistance and criticism is related to misunderstandings and misinterpretations caused by this complexity. Good leaders are aware of this and put extra energy and focus on communicating and explaining the complexity to those who are affected by it. They don’t make the mistake of pretending as if there is no complexity, as if things are seemingly simple. They don’t deliberately communicate about the reality in simple generalizations and in black and white terms. Nor do they use the complexity as justification for their actions. Instead, good leaders don’t want to make things look simple when they are not, but they don’t want to hide themselves behind the argument of complexity either. They don’t pretend they know the full scope of the complexity and all its consequences, when they do not. Instead they focus on explaining openly and honestly what they believe is the essence of the complexity and its potential consequences, what they believe should be done to create change, and why this is important. They invite the critics to exchange perceptions, experience, knowledge and ideas together, and to create a shared view on the complexity and on what to do to overcome its challenges.

They communicate clear values. Good leaders are persistent when it comes to their values. They see values as one of the fundamentals on which successful change is built. They pay special attention to communicating values, even when they deal with criticism. They don’t try to counter criticism by losing themselves in technical arguments and details, by showing their knowledge and expertise. Instead they explain the values on which they based their decisions and actions, and the importance of these values. By doing this they align people around these values and build a case for their decisions, especially when these decisions have unpleasant consequences.

If they have committed mistake, they admit them; they except that when the criticism is valid they need to adjust their decisions and actions. They show courage and are willing to take a risk while leading complex change, even when it turns out to be a wrong decision.

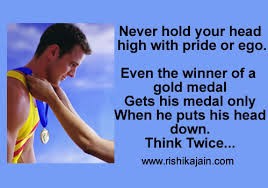

Most importantly, they understand that ego is one of the biggest barriers to people working together effectively. When people get caught up in their egos, it erodes their effectiveness. That’s because the combination of false pride and self-doubt created by an overactive ego gives people a distorted image of their own importance.

Egoists see themselves as the centre of everything and they begin to put their own agenda, safety, status, and gratification ahead of those affected by their thoughts and actions. That’s a deadly combination in today’s business environment, where organizations need people to work together collaboratively to meet the ever increasing expectations of customers.

The single most fact is that for all managers criticism is part and parcel of life.